Mitwold

The Pride of the Marches

Mitwold is arguably the richest of the Marcher territories. There's gold in the soil of Mitwold - the gold of rich harvests of fruit and grain. It has a substantial coast, scattered with small fishing villages and the occasional lonely watchtower. As one moves further inland, the rocky coast gives way to fertile chalk-soiled downs, with rich game-filled woodland, large farms, and prosperous market towns beyond. The largest settlement in Mitwold - indeed in the Marches - is the "town" of Meade, standing proudly at the mouth of the river that shares its name. More a small city than a town, Meade is in some ways the beating heart of the Marches.

When the other nations imagine the Marches, it is usually Mitwold they bring to mind - acres upon acres of well-tended fields and orchards, laid out like a grand patchwork blanket, scattered with villages connected by roads and dirt tracks. Here and there a lonely dolmen watches over the land around it, often marking a point of historical interest, or serving as a meeting place for the landskeepers of the adjoining area.

This is also the territory where many of the best known ball games are played, and it is a regular occurrence for some local dispute to be settled by over savage game of rugby, football or rounders. Some of the traditional inter-village or inter-household games go back centuries, having become regular fixtures long before the foundation of the Empire. Many have their own traditions - the people of Parkestown and Harwich in the Maiden Downs compete annually to determine the control of a prime stretch of grazing land between their two villages, for example,

More than anywhere else in the Marches, the households of Mitwold are engaged in feuding and bitter rivalry. The closer two households are to one another, the more likely it is that they are engaged in a long-running feud. Often the original cause of the feud is lost to history, having become a self-perpetuating state of affairs as each slight delivered by a rival becomes justification for the retaliation that follows. These feuds rarely lead to bloodshed - it is a rivalry of skinned knuckles not bloodied knives.

Recent History

Mitwold's history has been comparatively peaceful. Bregasland and Mournwold provide a buffer, protecting it from the martial ambitions of the Jotun. That is not to say it has been without incident; several times in pre-Imperial history the people of the Marches were at war with the people of Wintermark. Lonely dolmens and stands of ancient trees along the northern borders of the Meadows and Meade March mark ancient, largely-forgotten battlegrounds. From time to time, stories circulate of unquiet spirits around some of the barrow mounds - bitter Wintermark warriors interred in Marcher soil.

For the most part though, Mitwold has enjoyed the benefits of being a relatively safe place to live, secure in its prosperity - or as sure as any agricultural territory reliant on good harvests can be.

The disastrous failure of the Autumn harvest in 379YE was followed by a particularly harsh winter during which all the farmers of the Marches suffered significant losses in order to keep the Imperial armies marching. Then the Spring 380YE planting was hit with torrential rains and a vicious blight that devoured many of the seeds before they can be put in the ground. While the rest of the Empire was enjoying a burst of vitality and fertility, the farms of Bregasland, Upwold, and Mitwold were once again labouring under the yoke of a vicious magical curse that ruined the crops, sapped the life from the beasts in the fields, and spread sickness and hunger wherever it touched.

The plan to construct the Imperial Breadbasket began in the markets of Meade and received immediate support from market towns across the Marches. Lead by the people of Meade, the aldermen put their hands in their pockets - not as an act of charity, but as recognition of the fact the Marches prosper when the farmers prosper. It was an investment for the future, as well as an effort to "darn the rip" between the folk of the market towns, and the rest of the Marches. As a result, shortly before the Spring Equinox 381YE, work was completed on a network of granaries and storehouses across Mitwold as part of the Imperial Breadbasket great work. In addition to its work in securing the future of the Marches, this has helped to improve relations between the yeomanry and the residents of the market towns - reinforcing that even though they do not till the soil, they are still Marchers.

Shortly before the Autumn Equinox 381YE, an earth tremor struck Mitwold, its epicentre near the town of Wayford. At first, the effects seemed minor - a little damage to some of the buildings in Wayford - but shortly after creatures similar to ogres began to appear in the area. Investigations by Marcher heroes discovered that the cause of the raids - if not the earth tremor itself - was an unnatural creature, buried deep beneath the earth. "Bloody Jack" appeared to be some sort of horrible troll creature, no doubt the source of the local legends of Jack-in-Chans. The entity lay at the bottom of an old stone-choked well, bound with magical chains - chains that had been damaged in the earth tremor and were close to breaking completely. The creature remained a threat to Mitwold until the Summer Solstice 381YE. With the aid of the Winter Archmage, several brave yeomen made a bargain with the sinister eternal Tharim, allowing the subterranean beast to once again be bound tightly. A dolmen is due to be erected over the entrance to the well - the sooner the better in fact given that several foolish youths have already tried to gain access to the troll-creature's tomb in search of treasure.

The business with Bloody Jack also brought to light stories of the Marcher blacksmiths - legendary figures who combined a practical appreciation for metalwork with a calling for negotiating with eternals. The exact story is still garbled, but it appears that these capable magicians disappeared from the Marches so long ago they have largely been forgotten as the result of a deal with the Autumn eternal Estavus. Several Marcher scholars are currently looking into the situation, and working to secure the return or release of this uniquely Marcher tradition - presuming that is even possible after all these years.

Major Features

death of Empress Britta.

Meade

The largest settlement in the Marches is the city (technically a market town) of Meade in Meade March. Crowded around the mouth of the eponymous river on the shores of Westmere, Meade is not only the spiritual and administrative heart for the nation, it’s also a port whose ships deal in fishing, trade with foreign nations and sea defence against the barbarians through Westmere and the Gullet.

Meade is where yeomen from across the Marches come to spend hard-earned coin, and often plays host to foreign visitors from other nations. The lavish week-long Harvest’s End Festival takes place in Meade every Autumn, and sees the city fill with folk from all across the Empire. Still, Meade is not without its problems. Some yeomen look askance at the citizens, questioning how they can be proper Marchers given they live in a town rather than on a farm. To many of their critics, they are merchants, not true yeomen. They point to the scandal during the reign of Empress Giselle when several aldermen were implicated in a plot to secede from the Marches - a plot that never had much popular support but whose existence alone was enough to rekindle rumours that the folk of Meade are "not proper." At the same time, the aldermen of Meade know that their settlement is not even half the size of the great cities of the League, and this can lead to efforts to try and compete with the merchant princes of Tassato and Temeschwar with predictably disappointing consequences.

Still, regardless of the past and the attitude of some suspicious yeomen, the people of Meade are Marchers through-and-through. They are practical, stubborn people who hold fiercely to the traditions of the Marches. As their recent involvement in the formation of the Imperial Breadbasket demonstrates, when push comes to shove they look out for their own people - the people of the Marches.

In the wake of the death of Empress Britta in 376YE, semi-organised groups of bandits began to prey on traders traveling by land from Meade. By order of the Imperial Senate, in early 377YE a series of watchtowers and earthworks were constructed around Meade to help address this problem. The works were overseen by Bridget Eastville née Talbot (senator for Mitwold) as part of a larger plan to provide protection to towns throughout the Empire. While the defences are not sufficient to qualify Meade as a true fortification, they have already helped reduce brigandry throughout the territory.

The Bailiff of the Grand Market has a small office in Meade, although most title holders spend little time there (apart from to oversee the security of the grand market on the third weekend of each month). The Bailiff is an Imperial title auctioned each Winter Solstice through the Imperial Bourse that can be held by any citizen of the Marches.

Forte Fidelis

In 377YE Richard Tunstall, the Imperial Master of Works, approved the creation of Forte Fidelis in Golden Downs. It was one of only two castles approved by the Master before the Senate removed their ability to do so. Construction was funded partly by the Master's stipend (before it was removed by the Senate), and partly by money raised and donated by the Marchers themselves. Work on the fortification was completed shortly before the Winter Solstice 378YE.

The fortification was completed while the Jotun ceasefire was still in place as a counter to Mitwold's perceived vulnerability to attack from the Mournwold, once hostilities inevitably resumed. Surrounded on all sides by a deep moat, accessible only by a relatively narrow bridge. the castle has yet to see combat. It takes it's name from the Old Asavean motto of the Talbot household - "forte et fidelis." Following his retirement from Imperial politics, Richard Tunstall still serves as the castellan, ensuring that the castle is prepared for any potential invasion of Mitwold.

Hay

“The golden fields of Hay” appear in many a Marcher song. Hay is quintessential Marches, a small rural town set amongst rolling fields. Following the invasion of the Mournwold, the folk of Hay were been deeply concerned about the threat of further orc aggression. Several locals have formed themselves into the Hay Irregulars, an unofficial force dedicated to helping turn back the barbarians should they attempt a concerted raid. The Irregulars served with some distinction fighting off small bands of raiding Jotun, before the Mournwold was finally liberated in Autumn 381YE.

Hay is rightly famous for its fields of wheat, and for its bakeries. Many of the farmers of the Golden Downs bring their grain to market here, where a significant portion of it is used to make flour and bread products including the famous "Hay Huffer" - a crusty triangular bread roll with a thick, doughy texture designed to fill the bellies of labourers across Mitwold and beyond.

Wayford

A large market town at the confluence of the upper tributaries of the Meade. A layer of gritstone in between the chalk of the wolds means the river is wide and shallow, allowing livestock from the hills to cross, or embark on riverboats to Meade itself. Built along the southern borders of the Meadows, it is a bustling settlement known for its travelers inns and for its monthly cattle and sheep markets. Merchants visiting Meade pass through Wayford, as do Marcher traders exporting food and drink to the wider Empire. The town is quite cosmopolitan - there is a large transitory population of Winterfolk, League citizens, and Navarr coming to Wayford to travel.

All this propserous trade attracts its fair share of trouble, and the Bailiff of the Grand Market is regularly called upon to deal with bandits and brigands preying on trade along the roads that pass through Wargord. At the river fork stand several gibbets with a long and bloody history, notable in recent years for playing host to Red Walder and his outlaws, a plague on the Mitwold for many years finally brought to justice in 359YE following a week-long standoff in the Shepford Brewery near the Wayford Bridge. The town is also notable due to legends of a monstrous creature known variously as Jack-in-chains, Jack-of-Irons and Bloody Jack who is said to be buried somewhere nearby.

The Maiden Stone

An ancient dolmen that stands in a scorched area of land in a grove of ash trees. Every year before the Spring festival the farmers of the area weave the largest straw dolly known in the territories. The Straw Maiden, as the creation is known, is 12 feet tall adorned with wild flowers with intricate patterns of vines woven into her skirt. The Maiden’s skirt is hollow at the base and she is placed atop the dolmen. The landskeepers of the Maiden Downs then perform a night-long ritual designed to bring prosperity to the fields and flocks of the people of the Downs. The Maiden then stands in the grove until the end of Summer, visited by travelers who leave gifts of food, poppets, minor trinkets, and other offerings at her foot in the hope that she may bring them some small favour. Although the Maiden is exposed to all weathers and temperaments, she does not rot, blow away or decay in any way, staying as fresh and brightly golden as the day she was placed upon the stone. Then, at the festival of Autumn Harvest there is another ceremony, the culmination of which sees the Maiden set alight, burning until there is nothing left.

Needless to say, the ceremonies of the Maiden Stone are roundly criticized by priests of the Imperial Synod. There have been efforts by priests from outside the Marches to ban the practice, denounced as the worst kind of idolatry. The Sevenfold Path has occasionally attempted to get the Imperial Conclave to interdict the ceremonies without sucess. In 186YE and 247YE, the ceremonies were stopped for a short time but in both cases resumed less than a year later.

The landskeepers of Meadow Downs claim that they are simply performing the three powerful farm-blessing enchantments (Blessing of New Spring, Strong Ox, Golden Sun, and Gathering the Harvest) and that the gifts left by visitors are simply a harmless tradition. There is some evidence that the landskeepers also perform a rite in the depths of Winter without any witnesses; lurid speculation surrounds this ceremony.

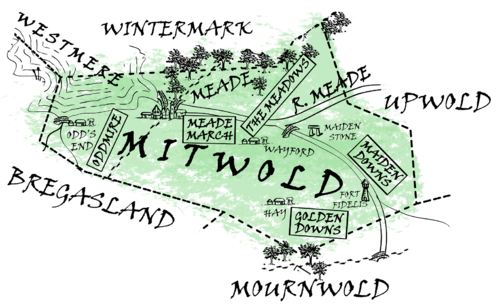

Regions

Golden Downs

The rich farms of Golden Downs are home to the prosperous village of Hay, as well as a number of smaller farming villages. It is also the location of the Silent Giant standing stone that watches over the surrounding fields - several other dolmens mark the old boundaries of one farm or another but the Silent Giant is the largest. For the last three decades, the Golden Downs has been in a state of war-readiness, expecting an invasion from the Mournwold - indeed the Jotun raided north into the region many times over the duration of the occupation. Citizen militia such as the Hay Irregulars prided themselves on their readiness to fight off such raids, even in the absence of organised Marcher armies. Many independent Marcher captains cut their teeth taking paid work protecting the rich farms of Mitwold. The need for such special forces was reduced significantly in 377YE when the Imperial Master of Works approved the creation of Forte Fidelis in Golden Downs. This fortification was completed shortly before the Winter Solstice 378YE.

During the Jotun invasion of the Mournwold in 349YE, many of the citizens of Green March fled north to the Golden Downs; a long history of good relations and familial ties between the two regions helped to mitigate any negative effects of this influx of landless yeomen. Unlike many of the Mournwold refugees the majority of these former refugees show little interest in returning to reclaim the land they (or more often their parents) lost three decades ago.

Maiden Downs

The Downs are covered in a patchwork of wealthy and prosperous farms. Some outsiders attribute the success of the farms here to the magic of the Maiden Stone, but the yeomen who work the land here disparage such suggestions. Rather, they point out, their farms are prosperous because they work bloody hard to keep them that way. Still, the Landskeepers of the Maiden Downs have a reputation for being a little peculiar, and to be significantly more secretive than those in the rest of the Marches - almost bregas in the words of some.

There are no large settlements in Maiden Downs - not even along the highway that links Wayford to Stockland. Farmers are as likely to sell their produce in either town, depending on which is paying the better price in any given season. This has lead to a few feuds between households of Maiden Downs and those of Golden Downs and the Meadows over what is seen as "a lack of loyalty to Mitwold."

Meade March

Often called the heart of Mitwold, Meade March is the location of the small city of Meade, built at the mouth of the river that shares its name. Meade is prosperous, and its port bustling, but the river is both too narrow and too shallow to allow passage to a navy (OOC Note: the region of Meade March does not have the coastal quality). While the aldermen have occasionally discussed dredging the river to allow the construction of a shipyard, there has never been enough support for such a large-scale undertaking. Wiser heads also point out that while a shipyard might provide a suitable anchorage for a Marcher navy, it would also mean that Meade was placed at risk of being sacked by a barbarian navy, should one ever appear, and that tends to end the argument.

Outside of Meade, the Meade March is covered with farms and scattered villages, and even a few small towns. The yeomen here have a somewhat undeserved reputation in the rest of the Marches for considering themselves "better" than everyone else because of their proximity to Meade - of giving themselves "airs and graces". A common stereotype that appears occasionally in plays and stories is that of the Meade yeoman who farms their field wearing a rich outfit, more suited to a feast day than a work day. There is little factual foundation to this prejudice - although many yeomen of the Meade March visit the city at least once a season and thus have access to a significantly wider array of goods and cloth than residents of more isolated parts of the Marches.

The Meadows

While most of this region is rolling farmland, the northern Meadows abuts the Wittal Grove of Kallavesa. The woodlands are home to at least one tribe of feni, but for the most part the Meadows is a peaceful, pastoral place. Before the Empire, however, there were occasional clashes between Marchers and raiders from Wintermarker along the border, and the northern woodlands still have an unsavoury reputation as being haunted.

South of the border, the forests that once grew in the Meadows were cleared centuries ago. Here and there between the farms however, a lone tree stands as a boundary marker and a silent reminder of a time when much of the Meadows was covered in trees. These so-called Lone Oaks are reminiscent in some ways of the dolmens found in other parts of the Marches. According to tales told across the Meadows, in the first years of the Marches the northern woods were home to terrible monsters who regularly attacked people trying to settle north of the Meade river. Eventually, however, a wily blacksmith made a deal with the ruler of the monsters. The creatures would leave the settlers alone if in return the Marchers stopped cutting all the trees down. In the end the Marchers had the last laugh however - they cut down almost all the trees leaving only a scattering of Lone Oaks - but by the careful wording of the agreement the monsters were unable to harm the people of the Meadows as they had kept to the letter of their bargain.

In addition to its farms and eerie trees, the Meadows is also well known for its herb gardens, especially in the north. In particular, the quality of True Vervain grown in the Meadows is generally held to be unmatched in the Marches. The herbalists of the Meadows are known to make occasional pilgrimages north to Wittal, in Kallavesa, to share lore and trade herbs.

Oddmire

Quality: Coastal

When the Marchers first arrived in Mitwold, Oddmire was extremely marshy. Several decades of work reclaimed most of the region, despite the best efforts of angry marshwalkers to stop the draining of the swamps and marshes. There are still some treacherous bogs in Oddmire, especially along the southern and western borders with Bregasland, but the majority of the region is fertile farmland. As is traditional in the marches, there are large numbers of farms here, but there are also a few more isolated communities built on the small, rocky islands that lie along the southern shore of the Westmere.

The most prominent settlement here is assuredly Odd’s End, a bustling fishing port. The fisherfolk of Odd's End are known to have something of a chip on their shoulder when it comes to the larger, more prosperous Meade. They fly their banner - a leaping salmon - proudly whenever they set sail and barely a year passes without a major row between fisherfolk from Odds End and boats out of Meade over fishing grounds. A well-respected monastery - Odd's House - stands near the port, dedicated to the virtue of Pride, and the monks there regularly encourage the people of Odd's End to stand up for their rights against the larger Meade.

Odd of Odd's End is a popular folk hero from the early days of the Empire, born around 45YE. She was an outspoken devotee of the virtue of Pride, and in later life founded the monastery that still bears her name. Settling her folk on the shore when the Marchers first reached the Westmere, declaring that this would be the place where she would end her days, she was instrumental in the draining of Oddmire among other significant deeds. A series of stories, popular with Mitwold's mummers, recount the many deeds of this folk hero, especially her battles against marshwalkers, and her rivalry with the aldermen of Meade.

Despite her popularity, there has been no serious effort to have Odd recognised as an exemplar by the Imperial Synod. When the matter has been raised, the abbot of Odd's End generally shrugs and responds with a variant of "We know she's an exemplar, why should we look to outsiders to confirm it?"

OOC Notes

- All the regions of Mitwold are under Imperial control.

- Forte Fidelis in Golden Downs is a rank one fortification.

- Under normal circumstances, the Imperial Breadbasket great work gives every Marcher character who owns a farm a share of 1080 rings. As of the Senate decision to amend the use of the Imperial breadbasket in Summer 381YE, the benefits are not being received as the effects are being funneled to support the Mournwold.

Henry Talbot sat with his back to the tumbled wall of the burnt out homestead, sweat plastering his dark hair to his forehead.

The flush of vigorous life had faded from his cheeks during the escape from the barbarians, but mischief still sparked defiantly in his eyes. Sun beat down and wisps of steam made thin halos about their heads. "Nothing you could have done Ned. Thank the boys for carrying me all this way... How long do you think?"

" It could be an hour, or as short as you..."

Ned paused as he reached into his pouch of herbs. A decade of hunts made him grab instinctively for his pike, the mating cry of a Bregesland Dove in the wrong season could only mean one thing.

"Cullach-A-Cullach!" Sounded to the right, accompanied by a gurgling squeal. A moment later two Orc scouts and a human slave burst from the bushes in front of them. Ned brought the pike to bear, but not fast enough.

The smaller of the two orcs, face split with a recent wound, shoved the slave into the pike and drove her body onto the shaft. Ned drew his dagger, but the orcs were on him before the sword was free. Not relishing the prospect of a standing fight they rushed forward and bore Ned to the earth.

In a flash decision Ned dropped the dagger, grasping the wrist holding a rusty knife and breaking the nose of the second Orc. Broken Nose rolled away from the melee, streaming blood and curses, while Split Face and Ned struggled over the knife.

Suddenly Henry was stood astride Split Face, Ned's dagger in hand. With a butcher's confidence he sliced Split Face's neck to the bone, drenching Ned in ichor.

Ned held fast to the rusty knife, taking it from unresisting hands. As he cleared his eyes Ned heard Henry grunt and the tip of a blade emerged from his stomach. Henry toppled and Broken Nose stooped over the to pull the notched sword free.

Roaring in fury, Ned kicked Split Face's body off and launched himself forward. The notched sword was trapped and useless between them, allowing Ned free reign with the rusty knife...

Ham came to check on them once the rest of the orc scouts were disposed of. Ned sat beside the ashen body of Henry Talbot, truely still now that he had begun his journey through the labyrinth. The remains of a human and two orcs lay in the remains of the herb garden. Not a word passed between the Cullach, just a look and a nod.

With great care they removed Henry's harness and hid it up the chimney of the homestead, suspended from the meat smoking hooks. Ham took the small antler handled knife from Ned's shaking hand and cut Henry's warm heart free from his chest. Ned knelt and filled Henry's mouth with Marcher soil, replaced in the oiled pouch by the heart. They closed his eyes and pushed the remaining wall of the homestead over him.

The fallen stones would conceal him from desecration and keep him from scavengers. Now they had to move on, their burden heavier than a dying friend.

"Rest well Henry Talbot, your march is done."